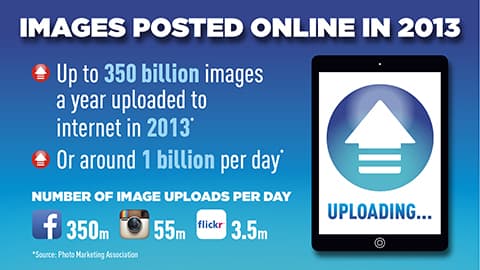

Up to 350 billion images were uploaded to the internet last year, according to industry estimates.

That’s more than 50 images for every person alive on the planet. If these were printed as 6x4in photos, and laid end-to-end, the line would stretch almost as far as Mars is from Earth.

Instagram alone says 55 million are posted using its photo-sharing service every day.

VIDEO REPORT (above): Is Getty’s photo rights policy fair? What does it mean? AP interviews industry experts (Graphics: Amateur Photographer magazine)

Images for nothin’, pics for free

Amid such

mind-boggling figures, the world’s largest photo agency, Getty Images, decided

to make 35 million of its pictures (almost a quarter of its entire archive) available for non-commercial purposes on websites and blogs, without

users paying a penny – a move many photographers were quick to condemn.

Internet users can post Getty images on Twitter, for

example, and if they choose later – buy larger versions of the ‘embedded’ photos,

for commercial use, by clicking on a link.

As well as promoting its brand, Getty is rewarded with

information about the websites that use its images and says it may place

adverts next to the photos that appear in the ‘embedded viewer’ window.

(Graphic: Amateur Photographer magazine)

A report by IMGembed, a body that aims to track and monetise online photos, claims that 85% of images are used without permission, according to an article published yesterday in US magazine Popular Photography.

As the colossal scale of online imaging threatens to

send copyright breaches spiralling out of control, was Getty’s move

predictable?

Yes, says Charles Swan, a media rights lawyer whose

practice has seen a ‘massive’ rise in cases over the past few years – largely

down to the proliferation of online images but also because people increasingly

use the Google Image search tool to detect infringements.

He feels Getty’s move is a ‘sign of the times, rather

than good or bad…’

Many copyright thefts not worth chasing

Swan, a director of the Association of Photographers

(AoP), adds: ‘A lot of [copyright] infringements are very minor. They are

people’s blogs… Getty isn’t going to sue them. Not many individual

photographers will.’

While many infringements may be ‘minor’, things can turn

truly nasty at the extreme end of the copyright lottery spectrum.

Last year, Indonesian photographer Hengki Koentjoro fell victim to having his image stolen online by a third party to win

a global photo competition. He is yet to receive an apology from the culprit,

eight months on.

Media rights lawyer Charles Swan

Joe Naylor is CEO of ImageRights International, a US

body that searches for online breaches and pursues compensation for

photographers worldwide. He tells us: ‘One of our photographers had a photo for

the cover of a book used more than 30,000 times online… It’s remarkable, not a

single legal use.’

The dust may have settled in the weeks since Getty’s announcement in March, but this has failed to quell the ire of rights

campaigners.

Getty contributors have since received verbal flack

over the move, from fellow photographers, according to one unconfirmed report.

‘Egregious’ move

Naylor, who describes Getty’s move as ‘pretty egregious’,

adds: ‘Photographers have supplied content under a certain understanding they

are going to be paid…’

Adding insult to injury, it seems, Getty admits it

will not tell photographers about where their images will be used – for now at

least.

‘Even if there’s no revenue, photographers want to

know where [their picture] is and who’s using it, because that could inform

them about what type of content they should focus on in future,’ Naylor says, pointing

out that Getty’s policy was rolled-out ‘unilaterally’ – giving photographers no

chance to opt out.

‘It’s not transparent, which is not a great way to

build a relationship with your contributors.’

In response, Getty tells AP it will ‘explore’ future

data-sharing options.

‘It’s nothing to do with little bloggers’

Also still seething is Jeff Moore, chairman of the

British Press Photographers’ Association (BPPA). He sees no silver lining.

‘If someone owns something [an image] it is up to them

what happens to it….

‘It’s nothing to do with getting fivers and tenners

off little bloggers… whether that

opposition is [agency] Rex Features or 10,000 freelance photographers around

the world… It’s just another way of [Getty] trying to destroy the opposition…

To me, that’s what’s behind it.’

Photographers not paid

Royal

Photographic Society (RPS) director-general Michael Pritchard is more

diplomatic: ‘I think it could be beneficial to photographers because it could

allow them to commercialise work…

‘That

said, the other side is that photographers are not going to be paid for work

they might otherwise have sold.

‘At

the moment I think the jury is very much out and I don’t think we will see how

the situation plays out for another three, six or even nine months.’

Magnum already allows free use

The idea of allowing the public to download

non-watermarked images, for free, is not new however.

Two years ago Magnum

Photos revamped its website to allow users to download images for ‘personal

use’ and blogs.

‘The benefit to Magnum is that we want people to

engage with the work on our website rather than through Google and so on,’ says

a spokesman.

‘We felt watermarks didn’t really protect the images,

as so many of them are out there anyway. We want to draw people to Magnum so

they can engage with what we are up to.’

Magnum declined to comment on Getty’s decision.

The AoP, which serves to protect the rights of

professional photographers, forecasts an unwelcome side-effect.

It warns that photographers pursuing future claims, over

illegal use of images on blogs for example, may find it hard to prove a loss because

Getty is now providing pictures free of charge.

Public perception fears

The AoP fears it also sends the wrong message to the

public and ‘perpetuates the unhealthy idea that images are available for free

use’.

This is echoed by RPS’s Michael Pritchard who adds:

‘As we know and what Amateur Photographer

has been so good about saying is that copyright is important. Photographers

should be protecting their work and this is, perhaps, the one area where the

Getty move falls down…’

The RPS asserts that the term ‘non-commercial’ is also

open to question’, warning that any ensuing confusion may escalate infringements.

‘Getty… has come up with a definition that’s quite

loose in many respects and, from the public’s point of view, most people are not

going to read the terms and

conditions…

‘I suspect the use of the images is going to be so

massive that [Getty] is not going to be able to control, in a big way, how those

images are used’.

Keeping a watching brief: The RPS’s Michael Pritchard

‘Wrong direction’

UK photojournalist Jonathan Mitchell edits the Atlas

Photo Archive. Speaking shortly after Getty’s announcement, he said: ‘It’s

definitely sending people in the wrong direction.’

Moore agrees, as does Nottingham-based photographer and outspoken rights

campaigner Pete Jenkins who says Getty has capitulated to the ‘abandonment of

international copyright law’. He fears it will lead to a rise in copyright

theft.

Jenkins admits he did not see it coming. ‘Many

bloggers and other internet users have been working on the basis that everything

is free on the internet… Will would-be infringers realise that copyright laws have

not actually changed?’

It ‘devalues

photography’

Swan doesn’t expect it to deepen any public perception that images are copyright-free, but concedes that it ‘devalues

photography’ – a view echoed by Mitchell.

In reality, says Swan, the commercial licensing option

may promote the idea that photos are copyright protected.

Naylor explains further: ‘The fact [Getty] are

defining a certain set of images as free implies that there’s images outside

that set that are not free.’

Getty advertising spin-off

Getty reserves the right to place adverts in its Embedded

Viewer, without the photographer seeing any return.

Even if advertising revenue filters through to Getty contributors, Naylor doubts whether it would be ‘meaningful’

and, in any case, says it would worsen the downward pricing pressure in the market for professional images.

‘From a pure business perspective you can’t fault

[Getty]… This is a new way to monetise their content for all non-commercial

uses. It’s just that it is at the expense of the contributor…’

Any good news?

While, the prospect of future commercial licensing

would benefit all, this comes with a ‘big if’, cautions Swan.

Neil Turner, a vice-chairman of the BPPA tells AP: ‘We

work in a market-driven economy but, essentially, this can damage lots of

individual creators and eventually it’s going to trip Getty up as well.’

Others are more positive. Despite having his copyright

breached more than 130 times, AP reader Graham Stephen sees benefits, beyond

those for social media users and bloggers.

‘If Getty’s initiative gains traction then this could also

be good news for creators of original photographic content too, if it can raise

general awareness of image licensing concerns.’

Getty photographer: It’s a ‘positive thing’

The RPS is also upbeat. ‘We welcome the move in terms

of its regularising the illegal use of images and ensuring that photographers

are credited for their work…’ says Pritchard.

Getty contributor Ron Galella, in a statement released

through the agency, adds: ‘As professional photographers, we can never stand

still and resist change that has already happened…

‘When the landscape changes around us, we must be

prepared to recognise that, move on and embrace our next opportunity… Anything

that helps more photographers’ work to be seen by a greater number of people is

a positive thing, especially if that work can be consistently credited and

recognised, be it artistically or editorially.’

Will people want it? Jane Fonda does…

Beyond the fear and loathing, there are doubts over

whether it will prove a hit for Getty.

‘Buyers don’t go to personal blogs to buy content,’

asserts Naylor.

Swan also questions its popularity: ‘If you want to

put a Getty image on your website or a blog which is non-commercial, it will

come out in a format where it will have a big Getty logo on it… How many people

will actually want that?’

Getty is yet to talk numbers, but we know that Jane

Fonda is among the early adopters. The under-fire agency was quick to reveal

that the Hollywood star used Getty’s tool to post a photo of herself on her own

blog on 23 March.

Jane Fonda was among the first to use the Getty tool

Neil Turner doubts it will deliver the ‘shop window’ he

says Getty is hoping for. ‘Photographers work is quite easy to see anyway and

anyone looking for a specific image on a specific topic doesn’t need a Getty

account to browse through the Getty library.

‘So the idea that someone might stumble across

something on a blog somewhere in Texas and then go “wow! that’s the image for

me, I’m going to use it in a multi-thousand pound marketing campaign” is a

pretty big jump to make frankly.’

Photojournalism in jeopardy?

There

are other dangers too. Will smaller agencies pay the price as other agencies

follow suit? Or worse: will it damage

freelance photography and threaten photojournalism itself?

Turner warns: ‘Getty will have set a bar that other

agencies will have to try and follow, so I predict that you are going to get

other agencies following suit, with embedded images, which is not the way to

make this marketplace a viable concern…

‘Will Alamy follow, will Corbis follow? Who knows? But

what we do know is that the photographers concerned are the losers.’

The BPPA’s Neil Turner spoke to AP in a video interview

Small agencies under threat

Michael Pritchard is also vigilant, stressing that

specialist agencies stand a stronger chance of survival: ‘There is a potential

threat to the small stock agencies. Inevitably they are going to have fewer

financial resources to come up with their own scheme and, potentially, I think

we could see one or two of them say “it’s just not worth investment, we can’t

compete with the Getty’s of the world”, and… disappear.’

Alamy, which recently launched a service to ‘monetise

iPhone photos’, based around its new Stockimo app, declined to comment when

approached by AP.

Getty photographer Kevin Mazur is in no doubt that

others will follow Getty’s policy. In a statement released via the agency, Mazur,

a co-founder of press agency WireImage, said: ‘Evolving to embrace technology

that both encourages image sharing and potential new revenue streams, and

respects our rights as artists, is the way forward for the industry.’

A ‘trillion’ pics will be taken in 2014

With Flickr owner Yahoo predicting that nearly a

trillion images will be taken globally in 2014, image sharing can only go one

way, it seems.

The BPPA’s Jeff Moore sees only one outcome though. ‘It’s just another nail in the coffin of freelance

photography and there’s a lot of nails in the coffin already.’

[All photo credits: C Cheesman]

And here is the (old) news…

It’s not just blogs. News websites can use Getty’s

embed tool to garner images to illustrate an article, for free, provided it’s

in the context of a ‘newsworthy’ or ‘public interest story. ‘The problem with

this is that it goes way beyond people’s personal blogs and includes online

news sites in general including, for example, BBC News and Mail Online,’ says

lawyer Charles Swan. And, what about a news website where a story is no longer

topical, many months on – will the image still be allowed? Getty tells us that,

although it reserves the right to ‘remove and restrict’ image use, it currently

has no plan to issue an ‘expiration [date] due to news value’.

Picture data bonanza

Data exchange deals are nothing new. Last October

Getty struck an agreement with social networking site Pinterest where it pays

Getty for metadata, to include when and where a Getty image posted by users was

shot, and the photographer who captured it, for example. This allows Pinterest to

match the extra information against relevant adverts on its site, for instance.

Getty – which uses image recognition technology to identify its images on

Pinterest – says Pinterest users get to ‘have more fun’, while the agency’s photographers

get a credit and a cut of the fee.

CLICK HERE IF YOU WOULD LIKE TO MAKE A COMMENT ON THIS SUBJECT